Nikon Coolpix A

Background

Let’s start this site with a little background as to how your digital pocket camera came to be. It all started back when Oscar Barnack designed and built the first film camera that utilized 35mm movie film. That’s where the 35mm format came from – from movie film. The result of that experiment was the wildly successful Leica M system of cameras. That first little camera opened up a whole new genre of photography in that it was compact, easy to use and could “snap” pictures quickly without setting up a tripod, or having to look through the lens to set up the shot before loading the film.

It seems that since the beginnings of photography, there has always been a demand for a smaller camera, and over the years there have always been models available to take advantage of this market. Kodak built their business on this concept with their folding Brownie camera. As always, though, there are limitations and compromises inherent in making cameras small. In the days of Barnack – it was a compromise in image quality, as the 35mm negative was less than a 10th the area of a 4X5 inch negative. This was significant at the time, as film quality was not what it is today. However – the format stuck because of the images that were able to be made using it.

Film

Let’s fast forward to just before the big switch to digital. Film technology has improved so much that hardly anyone questions the quality of images taken with 35mm film anymore. It was the standard format for consumers and pros alike for many many years. And for compact cameras, there was no better compromise of size and quality than 35mm – just as in Barnack’s day, except the cameras got better and so did the quality of the film. Even so, for critical work, a larger film format produces superior results, and is the preferred choice for serious artists and professionals, and even with the advent of digital, many still prefer to use large format film for critical work.

So here we are in the digital age, with film being almost completely superseded by digital technology. So let’s take a look at how that technology works, and how it affects your ability to get a picture with a digital pocket camera.

Sensors

Digital cameras create images using “pixels” embedded onto a chip called the sensor. The pixels are the digital equivalent of grains of silver, which is what created the images on film. The tighter the grains of silver were – the smoother and more detailed the image was. This is why a larger piece of film created a more detailed image – because it would inherently have more grains of silver available to spread over the entire image. This concept is retained with the digital sensor as well. The larger the sensor, and the more pixels it has, the more detailed the image. So like film cameras, digital cameras have some limitations and compromises that must be taken into account when being manufactured. Let’s look at pixel count first.

You have no doubt seen the pixel wars going on in the advertising and manufacturing of digital cameras. There for a while, it was a case of “he with the most pixels wins.” At least that was what they wanted you to believe. The truth, of course, is much more complicated than that. First, there is a limit to how small they can make the pixels. So the manufacturing limitation of pixel size creates a limit on the number they can put on a sensor of a given size. The idea was to create as many pixels as possible on as small a sensor as possible to create a small enough camera that would still create good quality images at a reasonable price. Unfortunately though, there is another limitation regarding pixel density. The smaller the pixels, and the denser they become on the sensor, the more “cross talk” occurs between the pixels – which is a bleeding of the electrical signal of sorts, from one pixel to the adjacent pixel, and this creates what we see in the image as “noise.” What manufacturers have realized at this point in time (and this of course could change as fast as technology) is that upping the number of pixels on a small sized sensor has the result of diminishing returns.

Companies like Canon have actually reduced their pixel counts on some of their compact cameras for instance because the image from a sensor with fewer pixels is actually cleaner and more “useable” than that from a more densely packed sensor. So there is more to the story than just the number of pixels. The other factor as mentioned above, is size. Bigger sensors allow more pixels to be distributed over a larger image area, creating a more detailed image. Unfortunately, we are again limited in the manufacturing process, as the larger the sensor, the more steps are required to create it and the more it costs to produce. This is why large sensor digital cameras can be tens of thousands of dollars.

As if those limitations aren’t enough, there is still another factor that has to be considered in the creation of a small digital camera, and that is the lens. As the sensor size gets bigger, the corresponding lens has to get bigger as well – and this is the same with a film camera. Digital sensors have some special attributes that make this even more difficult. Unlike film, a digital sensor does not “see” light at an angle, as each of the pixels faces straight forward. So as light from the lens strikes the sensor at an angle, the pixels begin to fail to register it. This requires lenses designed to have a more direct and “straight” light path coming from the rear of the lens. This necessitates that the lens be further from the surface of the sensor than would be necessary on an equivalent sized piece of film. This creates a real problem for wide lenses, whose focal lengths create a focal plane that is much closer to the rear of the lens, and thus the sensor, and a much steeper angle of image projection than a normal or tele lens. Smaller sensors help mitigate this problem – and this is another reason that most small cameras have small sensors.

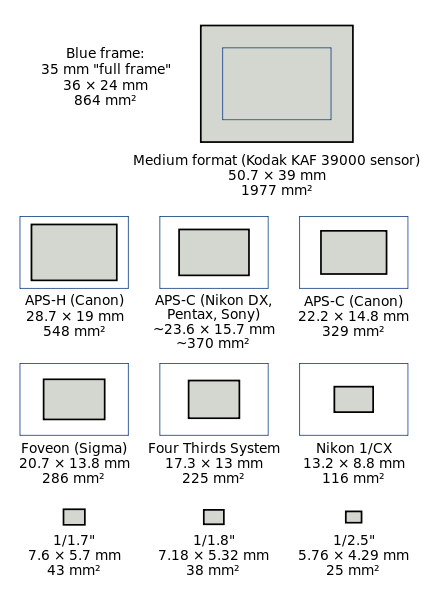

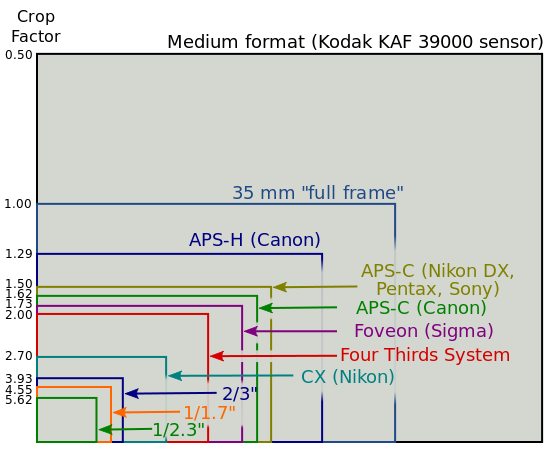

Ok – that being said, there are many different combinations of sensor size and pixel count available in the marketplace on compact digital cameras. If I could have the world – I would like a digital “twin” to the original Nikon Lite Touch (which I still have) that uses 35mm film and came with a 28mm wide angle lens. In the digital world – this would be a small digital camera with a “full frame” sensor of about 18-36 megapixels and a high quality 28mm lens. Because of all of the factors mentioned above – we are still waiting for such a camera – and if we ever get one (and I think we will eventually) it will cost a LOT more than the old Nikon Lite touch, even adjusting for inflation. Just take a look at Leica’s Q2 as an example, which has the full frame sensor and 28mm lens. Not only is it fairly large, it’s also quite expensive at $5000 as of 2020. For now – we’ll have to make due with 1/2 size sensors which are finding their way into some of the newer compacts like the Fuji X100V, minus the wider lens. Here are a couple of charts to put the sensor size issue into perspective. For a lot more detail and complexity – see this article on sensors at Wiki.

Internal Processing

You’ve probably heard the term “raw” thrown around in regards to digital files. What “raw”refers to is an unprocessed file that is coming directly from the sensor. What this means is that unlike film, a digital sensor doesn’t “see” the image being projected from the lens the same way as your eye does. What it does is take the light striking the pixels, and turn that into millions of electrical impulses which in turn are “interpreted” by the software in the camera and reassembled into the image the lens was projecting. Unlike film – which reacts chemically to the light striking it from the lens, a digital sensor simply converts the light striking it into zeros and ones, and it is up to the processor to handle the rest.

This is an important point with digital, because not only do we have all of the various factors already mentioned to contend with, we also have the internal software of the camera itself to consider. One of the things that many of these cameras share in common are the sensors. They often get their sensors from the same manufacturers and two different competing brands of cameras will often times be using the exact same sensor. You can bet, however, that the software processing the images from those sensors will be different – and this can affect the overall quality of the image. This is particularly important with jpeg files, as these are the standard output from compact cameras, and they can look very different depending on how they are produced.

Cameras that have an option for “raw” files allow you to save an unprocessed file in the camera, exactly as the sensor created it without any internal processing. What this means, is that you can now process this file yourself on your computer, using a software processing program of your choice. While I like this feature on a compact camera, I would not discount any camera for not having this feature, particularly if the files processed in the camera are of good quality. What processing a raw file yourself affords, is an opportunity to “have it your way,” and allows you to “hold the lettuce” if that’s your taste. In most cases though, this isn’t necessary, but a nice feature if you have the software and the skill to use it.

Another great feature of shooting “in the raw” is the ability to alter the settings of the image after the fact. All manner of things can be changed in the raw processing software – including sharpening, white balance and exposure to name just a few. This is as close to a negative as one can get in the digital world, as just like a negative – the raw image has to be processed – and thus can be altered during that phase. This is why pros make such a big deal about this feature – it has the intrinsic ability to save their bacon in a pinch if the color balance is off, or if they want to change one of the settings for that particular image.

Another aspect important to a raw file is dynamic range. Cameras don’t have the same ability to see such a wide range of brightness from dark to light as the human eye. So part of the processing in the camera is to compress this range into something that can be made into a picture. This was the big deal with Ansel Adams and his zone system. He was the first person to create a repeatable method for compressing the dynamic range of the scene to fit the limited range of the black and white film he was shooting. He did it in with a combination of exposure and darkroom processing of the film – but with digital, that processing happens in the camera. As part of that process – the raw image created will have the widest dynamic range that the sensor is capable of. From there, the camera will process it down to a compressed jpeg file or perhaps an uncompressed tiff file. So again – the ability to “self process” the raw file allows you to work with the full dynamic range of the capture, and make adjustments from there, and then save it as any kind of file you like.

Just a point : You do not need a raw setting on your camera! Most cameras produce good jpeg files right in the camera and this saves you the trouble of dealing with the raw files. I rarely use this feature on a point and shoot – and only on my DSLR if it is really necessary (and I think it will save my bacon). You may want this feature though if you are familiar with photoshop and want a little more dynamic range and control. Newer cameras today often offer a setting which allows saving two files for each image as they are shot – one as raw and one as jpeg.

Conclusion

So in a nutshell, what a small digital camera does, is take a wide dynamic range scene, convert it to 1’s and 0’s using a digital sensor, and rebuild that electronic data using an internal processing engine into a viewable “picture” of what the camera was seeing. How well this process comes out will depend on many factors, including sensor size, pixel count, lens construction and quality, the processing engine and most importantly – you!

Don’t let the marketing hype fool you. The number of pixels is just one factor to consider, and you may get better pictures with fewer pixels, depending on the configuration. Compare jpeg files coming out of the camera – as it is the processing software that creates these – and they will vary from brand to brand, even if they are using the same sensor. Also consider what your actual needs are. If you’ll be using it mostly for web/blog sites, then sensor size will really not be an issue. My first DSLR used a 2.73 megapixel sensor creating an image of only 6 megs. I bought it because clients were clamoring for it and I ended up using it a lot – so it fit the bill.

The ability to shoot “in the raw” is nice – but mostly unnecessary on a point and shoot (IMO) – although it could be a deciding factor for some who want more control of the final outcome using their own software to process the final image.

Shameless Plug

You can support this site by using the links on this or any other page to get your stuff from Amazon or Adorama! Bookmark the page once you have clicked on the link and each time you purchase something it will contribute to more articles and information. Likewise – you can donate via Paypal as well here:

Thank You!